Nosferatu

by Martin Chetlen

On November 16th, the VSO, as part of its Chamber Series, presented the silent film classic, Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror with a music score arranged by regular VSO contributor Rodney Sauer and performed by him and members of the VSO.

Many films might be passed off as “classic” but this one truly is. One of the most famous films ever made with some truly iconic scenes. It was released in 1922, in Germany, written by Henrik Galeen based on Bram Stoker’s Dracula (and directed by F. W. Murnau. An issue that haunted the film was that the makers did not get permission to base the film on Dracula.

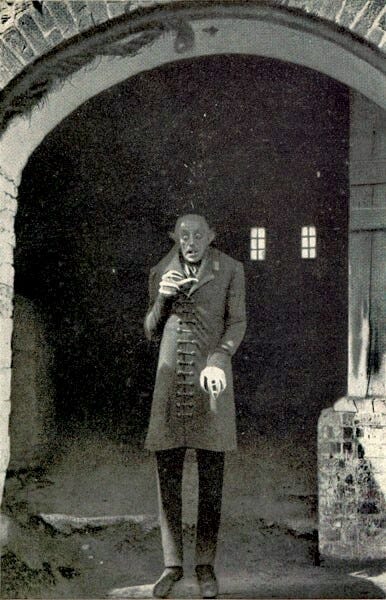

Another iconic part of the film is the portrayal of Count Orlok, the vampire, by Max Schreck. Schreck’s makeup and performance are so convincing that there still is a persistent (but false) story that there really was never a actor by the name of Max Schreck and the lead is done by an actual vampire that Murnau found. (In 2000, the film Shadow of the Vampire, used this legend as the basis of that film.)

Here, from Wikipedia.org, are two images of Schreck as Orlok:

The production was done on a tight budget, as were many German films of the same period. Some of the restrictions were creatively worked around through the use of non-realistic sets in a style known as German Expressionism. In German Expressionism sets were eerie, stark, menacing as well as cheaply painted and built. The entire expressionist approach became highly influential especially after German filmmakers fled to Hollywood during the Nazi era.

The photos show that Schreck does not look like the Bela Lugosi vampire famous from Tod Browning’s 1931 film. What was the influence in Nosferatu? Let’s look at a very short history of vampires in European literature.

The German word Nosferatu means undead – a synonym for vampire (or vampyre or vampyr). Legends of such creatures are ancient and worldwide. The first mention in European literature was in 1746 in a work with a long title by the French scholar Dom Augustin Calmet. Calmet traveled through Eastern Europe during a period of vampire scares gathering a large amount of material including sightings and exhumations.

Calmet’s work had wide circulation throughout Europe and was discussed by scholars of the time. Calmet’s folk vampire was thin, ugly, pale and utterly terrifying feasting on blood. This points to Murnau’s source for the Orlock makeup.

The first major literary vampire came about because of a challenge. In a now legendary story, in June 1816 poet Percy Shelley, his mistress Mary Wollstonecraft, Mary’s stepsister Claire Clairmont who was Lord Byron’s pregnant mistress and John Polidori, Byron’s personal physician were at Byron’s villa in Italy. Byron was probably the most famous author in Europe. His works were flying off the shelves, and he was being pressed by his publisher to write material he had already promised. Hence, Byron’s decision to rent an Italian villa. Shelley and Mary decided to visit and spend time with him and Claire. Mary was 18 years old at the time and had been with Shelley for about 2 years. They could not marry because Shelley was already married. (Shelley’s wife committed suicide later that year so the happy couple could then marry.)

The company had been reading German Gothic stories. (Gothic novels are considered to have started in 1764 with Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto. They became very popular, featuring creaky old castles, evilly usurped nobles, and supernatural happenings meant to right the situation. German Gothic tales were considered more explicit and lurid than English ones.) After doing this, so the tale goes, Byron challenged each person to write a ghost story.

The only 2 who complied were Mary and John Polidori. Mary wrote by far the most famous book, one of the most famous ever written, under her now married name, Mary Shelley. The book: Frankenstein; Or, The Modern Prometheus.

John Polidori’s novel while much less known, was very influential. It was based on what Byron started to write as his contribution to the challenge, Augustus Darvell. Byron started on this then abandoned it. Polidori got Byron’s permission to use the fragment as the basis of his own contribution, The Vampyre (published 1819).

The Vampyre is seen as the first fictional vampire tale in European literature. Polidori’s vampyre was modeled on Lord Byron. Lord Ruthven was urbane, educated, well-traveled, an unprincipled seducer of women who rewarded vice and punished innocence. Rejecting Ruthven meant the ruin of not only the one who rejected him, but their family as well. This was very different from the Calmet vampire. Calmet’s vampires were rustic and acted locally on peasants. Polidori’s vampyre was well connected, dressed stylishly, and wealthy. Someone who could mix with the elite looking just different enough to be considered fascinating.

Polidori’s story led to an interest in vampires in literature. The next major literary milestone was a now almost unknown work called Varney the Vampire: or, the Feast of Blood (1845). Its reputation today is as a very, very long nearly interminable book that was atrociously written. However, Varney was initially not meant to be a book. It was a “penny dreadful”. Penny dreadfuls were cheap magazines meant to furnish a reading public with stories. People, in English cities, were more literate than in the past even at the lower strata of society. They wanted reading materials and publishers were eager to supply it. The issues came out weekly with serialized stories. Writers churned out stories as long as people were willing to buy the issues. Deadlines were so strict that sometimes story chapters would be written in the magazine offices. As each page was finished, it would immediately be taken to be printed.

Authors were of no real importance. Usually, they were not even identified leading to disputes today over who wrote the stories. Publishers had no problem switching authors associated with a story in order to meet deadlines. The author of Varney is considered to be either James Malcolm Rymer or Thomas Peckett Prest. As of now, Rymer appears to be the frontrunner.

Varney was one of the two most popular penny dreadfuls. It ran for about two years in 109 issues. (The other was String of Pearls (1846). It was completely revised in 1878 and published as Sweeny Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet Street.)

Varney starts out as an Orlok-like vampire but transforms into a more Ruthven like figure. Eventually he becomes an almost sympathetic figure who is tormented by his horrible curse and wishes to be rid of it but can’t. Throughout the saga he seesaws between torment and horror. He sometimes becomes so angry that he is even more bloody and vicious. Then he has regrets and rues his fate. Finally, not wishing to continue and realizing that no ordinary means can end his existence, he throws himself into Mount Vesuvius.

In Varney there are a number of innovations in vampire lore development. Varney can be charismatic and sympathetic. He realizes he is a monster and wants to change but cannot. Varney also introduces the motif of the vampire’s hypnotic eyes.

Perhaps the 19th century’s best vampire story is Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s Camilla (1872). Camilla is a female vampire who seduces Laura. (Yes, there are very strong lesbian themes in the story.) Camilla is beautiful and calculating. Of course, in the end, Camilla is defeated, and Laura saved.

The popularity of vampires was such that even Sherlock Holmes got involved in The Adventure of the Sussex Vampire (1896, not published until 1924). Of course, there really is no vampire in this story and Holmes again saves the day.

Bram Stoker acknowledged that Camilla was an influence on Dracula (1897). Dracula was very successful, but another book published the same year was even more successful, Richard Marsh’s The Beetle. The books have a number of similarities. Both feature a outsider, the “other”. The eastern European Dracula and, in The Beetle, an ancient Egyptian mummy. Both are supernatural and malevolent. Both sexually threaten “pure” white upper-class English women. Both may have successfully sexually possessed those women. Both are defeated and women rescued, although, in Dracula, one is not rescued and becomes a vampire who must be destroyed.

Eventually, Dracula becomes extraordinarily popular, and The Beetle forgotten. Plays based on Dracula were quite popular. The first known movie was in 1921, a Hungarian film called the Death of Drakula. No known prints of the film have survived. Nosferatu was the next film to be based on Dracula. It is still considered by many to be the most artistically successful film based on the book.

However, Stoker’s widow Florence, sued for copyright infringement and won. All prints of the film were ordered to be destroyed. Fortunately, some prints survived.

There was a music score originally written for the film, but it is mostly lost. There have been attempts to restore it. Other composers have also written scores. For the VSO showing, Rodney Sauer arranged a score to be played in the theater as the film is being shown.

For More

Most, but not all, the material on the film is from Wikipedia.org

Polidori, John. The Vampire and Other Tales of the Macabre. Edited with an Introduction and Notes by Robert Morrison and Chris Baldrick. Oxford World Classics. 2008.

Shelley, Mary. Frankenstein. (The New Annotated). Edited with a Foreword and Notes by Leslie Klinger. W. W. Norton. 2017.

Rymer, James Malcolm. Varney the Vampire: Or, The Feast of Blood. Introduction and Notes by Curt Herr. Zittaw Press. 2008.

Le Fanu, John Sheridan. Best Ghost Stories of J. S. Le Fanu. Edited with an Introduction by E. F. Bleiler. Dover. 1964. This collection includes Camilla. I very much recommend Le Fanu’s stories in the Dover editions edited by Bleiler.

Marsh, Richard. The Beetle. Edited by Julian Wolfreys. Broadview Editions. 2004. Also includes an introduction and excerpts from a number of late 19th century sources pertaining to the book and its themes.

Stoker, Bram. Dracula. (The New Annotated). Edited with a Forward and Notes by Leslie Klinger. W. W. Norton. 2008.

Disclaimer: The above constitutes my outlook and opinions and does not imply any agreement or endorsement on the part of the VSO, its Board of Directors, musicians, or staff.